Exaucé: Ballet Studies by Édouard Lock is an exhibition of photographs by the acclaimed Canadian choreographer, filmmaker, and photographer.

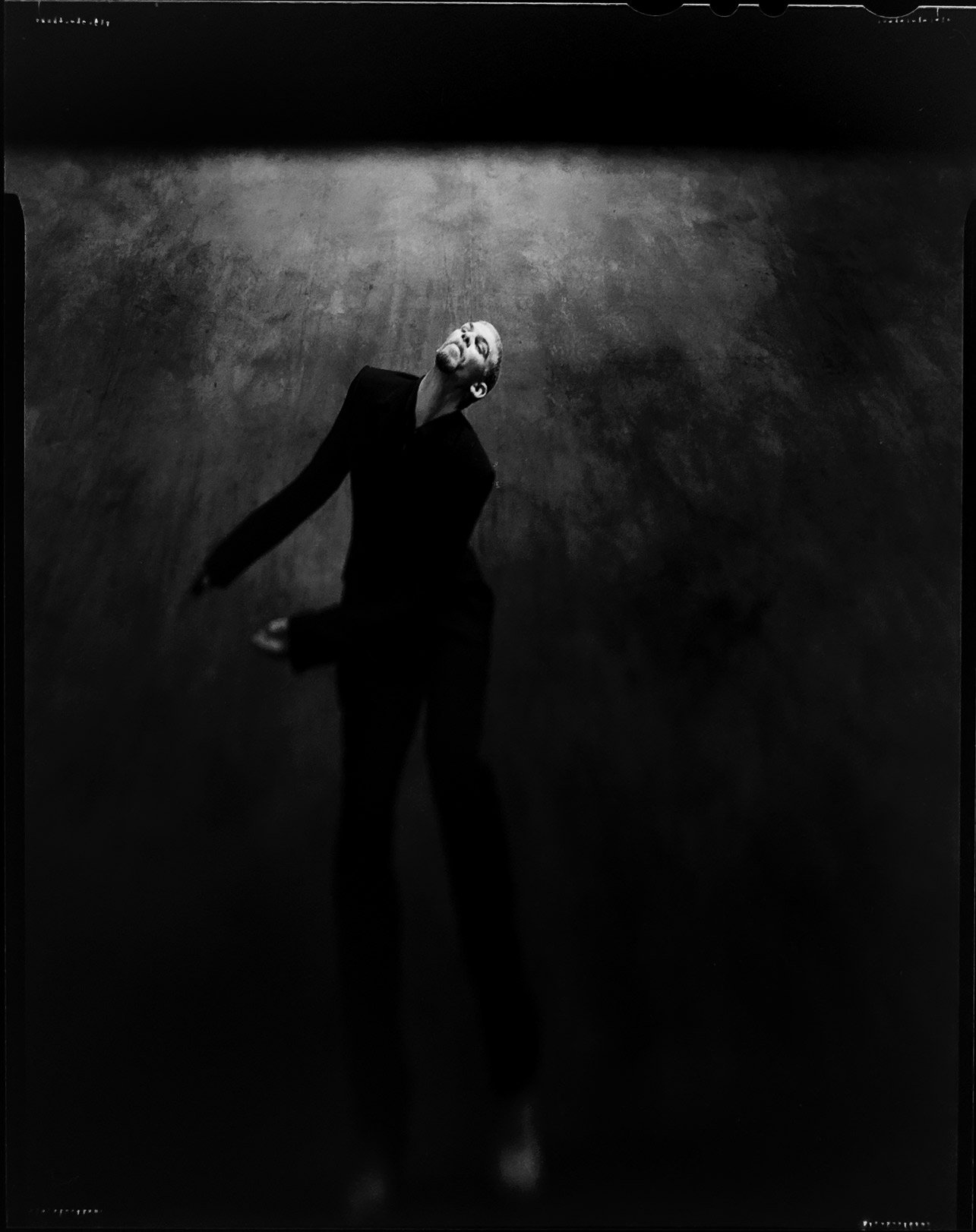

Presented publicly for the first time, this collection of powerful black-and-white images taken in 1998 captures the intricate relationship between dance, movement, and perception. Lock’s photographs push the idealized aesthetic of ballet to the extreme, blurring the lines between clarity and ambiguity. Inviting viewers to engage with the dancer's form as an object of subjective interpretation, Lock reveals his unique perspective on dance and photography, and challenges viewers to embrace the mystery inherent in the moving body.

Édouard Lock is an internationally renowned artist and founder of LaLaLa Human Steps. He has collaborated with some of the world’s leading dance companies, David Bowie, and Frank Zappa. Lock has received numerous prestigious awards and directed films that premiered at international film festivals.

Presented by Atelier Next Door (AND1357)

Produced by Vickie Fagan

Supported by Margaret Nightingale, Joan & Jerry Lozinski, Don & Marjorie Lenz, Jane Spooner, Dance Collection Danse

Curated by Francisco Alvarez

“ The photographs presented in this exhibition, taken in 1998, were created to publicize my contemporary dance company’s transition to ballet pointe technique and as a wink to both its past and future around this pivot point.

Although I had previously choreographed ballets on pointe for other companies, this marked the first use of the technique for LaLaLa Human Steps.

The resulting ballet, titled Exaucé, incorporated pointe as an additional choreographic tool rather than as a defining aesthetic.”

These images were designed to enhance and distort the body parts most associated with ballet – primarily the legs. Using a 4x5 camera with bellows, I tilted the film plane to produce spatial distortions. The elongation was most pronounced at the lower part of the image, tapering to natural proportions in the midsection, while the upper body exhibited reductive distortion. This approach magnified the idealized aesthetic of ballet to an extreme.

Unlike my usual approach to dance photography, which relies on capturing moments without interfering with the dynamics of the movement, these images required a more deliberate approach. The dancers paused in their positions, oscillating between stillness and a slight loss of balance. It was in these transitional moments, where lines softened, that I found what I was looking for. Another approach involved lengthening the choreographic sequences, which provided other opportunities for visually engaging transitions.

With no option for multiple takes, each shot involved loading the film, ensuring the distortions affected the intended body parts, and confirming the dancer's distance from the lens. There was room left for “mistakes,” which sometimes led to new options and new approaches we had not anticipated. The out-of-focus areas were just as significant as those in focus, necessitating a slower, more methodical overview of the positions to respond to these constraints.

Traditional ballet lines often proved ineffective due to the lens’s distortive logic; for instance, a high leg extension approaching 90 degrees resulted counterintuitively in a shortening of the limb. Therefore, only leg extensions below 45 degrees were viable. The approach to the ballet that these photographs publicized prioritized other types of distortions, such as complex movement patterns or “impurities,” speed, or shadows, to present the body as a sum of details too great to understand, rather than as an idealized construct.

I believe the body in movement transcends quantifiable templates like proportions, gender, size, and age. Thus, these photographs distort in alternate ways to the stage version – which is why I described them earlier as a wink.

These images also symbolize the historical ballet landscape the company was entering, evoking a sense of memory. I intentionally left parts of the frame dark, reflecting the inherent incompleteness of memories. As well, dance lacks a formal recorded history, unlike music, which has a comprehensive system of notation. This absence of documentation echoed my approach to both the photographs and the associated ballet, where the dark areas invite the viewer/audience to insert their own contributions into the shadows.

Regarding the use of pointe shoes, height conveys authority on stage, a quality enhanced by pointe technique, which is often misinterpreted as fragile. This technique is non-gender specific as the men in the company would also dance on pointe in subsequent ballets, demonstrating equal proficiency.

— Édouard Lock